The death and life of a great American bookstore

September 12, 2011 12:47 p.m. EDT

Ann Arbor, Michigan (CNN)

-- The End.

It seems wrong to begin a story like that, doesn't it? Particularly a story about a bookstore. It should begin "In the beginning," or "Once upon a time," or "It was love at first sight."

Especially "It was love at first sight."

After 40 years in business, Borders No. 1, the company's original Ann Arbor store, is scheduled to close on Monday. By late August, posters on the windows declared, "NOTHING HELD BACK!" -- and that meant the fixtures and furniture as well. The goods -- books, but also games and puzzles and teddy bears and throw rugs -- gave off the sour tang of a picked-over flea market.

A lonely security guard stood watch; he was added just recently, an employee said, after a shoplifting incident.

Borders Rewards customers have been receiving e-mails for some time now, ever since the chain declared bankruptcy and announced it was closing its 399 remaining stores. A month ago it was "30 to 50 percent off!" Now it's "60 to 80 percent off!"

There was recently a sign taped to No. 1's front door. It said, "Now Hiring: Apply Online at Borders.com." It was serious -- the liquidators needed to hire part-time help -- but it seemed like a sick joke.

What happened to the love?

"Borders used to be chockablock with books," said Jonathan Marwil, a University of Michigan history professor and author of a history of Ann Arbor. "It has increasingly looked less like a bookstore than a bowling alley, with its wide-open spaces. Now they're selling children's dolls on the front counter. It's really pretty grim."

It was a place where employees were devoted to their jobs. They prided themselves on their knowledge of their assigned sections -- and everybody else's. It was a gathering place and community center, just up the street from the university's main campus.

"We worked when we didn't have to work because we didn't know we were working. We would go into the store when it was closed to do more work," said Sharon Gambin, who arrived for the 1982 holiday season and went on to hold several positions during a three-decade career. "That's how much we loved what we did."

It's an odd thing to mourn for a store. Mourn for the employees who have lost their jobs, yes, but the store? Just another box on the roadside. Hundreds more like it. Move it along, capitalism.

Woolworth is long gone; few were saddened at its passing. Circuit City went belly up; silence. Great downtown department stores have vanished, changed names, disappeared to that Great Retailer in the Sky. (Jacobson's, the upscale department store that once occupied Borders' East Liberty Street storefront, is but one example.) With rare exceptions -- the late Atlanta newspaper columnist Celestine Sibley once wrote a valentine, "Dear Store," to the city's now-defunct retailer, Rich's -- the public yawns.

They'll probably soon forget about Borders as well. To most of the country, it's just another big-box chain, another in a series of disappearing strip-mall storefronts. Indeed, there's an irony in its demise, for as Borders is blamed for killing off some local independents, now it has been done in by Amazon and the Internet. The circle may go 'round again: Former customers may turn to independents, if their towns have them. Or, if they rule out their local chain, maybe they'll just go back to browsing on Amazon.

A shame, because when done right, there's something about a bookstore.

It's a library, a gathering spot, a refuge, a journey. Often it's small, maybe an 800-square-foot storefront jammed into a city street. Or it's idiosyncratic: an old house or converted barn, a rambling lobby or strip-mall space. It may not even be in your neighborhood, but that's where you go.

At its best, it's crowded: sometimes with people, always with books -- books stacked to the ceiling. Books lined up in bookcases. Books spread out on tables, highlighted on platforms, displayed in twirling, 5-foot-high wire racks.

Don't know what you're looking for? That's part of the adventure. A bookstore is governed by serendipity. You walk in and the world falls away. There's no rush. It's just you and the books, these pockets of words and paper that somehow transport you to a different place.

The best bookstores have a certain feel, a certain comfort to them. They're stately but not forbidding. The employees are a mix of the young and the eccentric, college students and lifers. The front of the store features their recommendations, a little offbeat, a little intriguing. If you're looking for something specific, they know where to find it; if you don't know what you're looking for, they can be your Virgil and Beatrice, guiding you through the world.

It is a place with a soul.

For much of its 40-year history, that was Borders. Though it was a chain, with hundreds of locations around the world, during its best years it maintained the feel of a great, expansive local bookstore, the 800-foot space multiplied by 10 or 20 (and much better organized). The choices were manifold, the employees passionate, the adventure always beginning.

In some towns and cities, Borders was it.

"I find in books a comfort and a companionship, a refuge from an urgently insistent world," wrote Ann Miller in the Longmont (Colorado) Weekly about the closing of that town's Borders, its only new-book bookstore. "I am worried about the folding of bookstores like Borders and the lost opportunity for browsing. ... There was no better place for grazing the written word and for meeting the best of friends."

Joe Gable, who managed Store No. 1 from the mid-'70s to the mid-'90s, puts it more simply.

"My goal," he said, "had always been to make the Ann Arbor Borders the best bookstore in America."

'Google-y' questions

Joe Gable came for love, too.

Joe Gable, right, set the tone for Borders. Robert Teicher, left, was the chain's longtime fiction buyer.

"I figured I'd work in the bookstore while I did the research. So I got a job at Borders clerking for $2.50 an hour," he recalled. His suffer-no-fools demeanor gets edgy when discussing Borders' later problems, but it softens when talking about the early days. "I had worked for a used bookstore in Madison while I was a graduate student, and I'd always loved books and the book business. And it just happened that the book business got really interesting and (Borders) evolved. ..."

By the time Gable arrived, Borders had been in business three years. Tom and Louis Borders, the brothers behind the name, both had U of M connections -- Tom had done graduate work there, Louis undergraduate studies. They opened a bookstore, the story goes, after spending $500 on a collection of books at an estate sale. (Tom is now an investor based on Austin, Texas; Louis, who founded the dot-com firm Webvan, is based in northern California. Tom declined a request for an interview; Louis didn't return phone messages.)

Ann Arbor, the kind of college town that describes itself as "six square miles surrounded by reality," was a scruffier place then, but in the 1970s -- as today -- it was one of the best-read cities in America. After short stays in other downtown locations and a change in focus from used books to new books, the brothers moved to a two-story, 10,000-square-foot storefront -- a former men's clothing store that dated back to the 19th century -- at 303 S. State Street.

Ten-thousand square feet. To sell books. It was an astonishing amount of space. "We're talking about 1974," said Benita "Be" Kaimowitz, who began work at Borders in 1975 and eventually trained the store's personnel. "There were no big bookstores." Kaimowitz, who moved to Ann Arbor in 1970, said she "went down there and just parked myself, and waited to get an interview."

Gable arrived just before the move.

"He had a vision of what a bookstore should and actually could be," said Jeanne Joesten, who joined Borders in 1986 and has held several positions over the years.

As manager, he kept the book-loving staff on their toes, highlighted some of the more obscure corners in the store's 100,000-title stock, went through the previous day's sales. He unpacked boxes and oversaw displays. He arrived early and stayed late.

"I saw this man every single morning sweeping the walk," said Gambin.

The Borders brothers had a feel for business. In the era before personal computers, Borders kept track of every single title on three-inch-square punch cards. Inventory was deep and rich. The inventory approach, an innovation of Louis Borders, led to a separate business, Book Inventory Systems, which the company supplied to other major independent book vendors. Tom Borders oversaw the store.

But it was Gable who reveled in books.

That often meant bucking the tide, not difficult in a countercultural college town that had been a center for the antiwar movement. Borders' employees, a crew of well-educated individuals who had to pass a qualifying test, were assigned specific sections and empowered to oversee them. Everybody cleaned the store; everybody pitched in on customer service.

Take the quiz: Could you have worked at Borders?

And everyone took pride in their knowledge of literature, science, publishing and, well, knowledge.

"Pre-Google, there was a spot near the front of the store where I could stand and say out loud almost any Google-y type question, and somebody within earshot would know the answer," said Kaimowitz.

The store's staffers included Steve Adams, the king of the sci-fi section; Sven Birkerts, who went on to become a well-known essayist; and poet Keith Taylor, who now runs the creative writing program at Michigan.

The store was richly stocked with works from small presses and university publishers, and often sold more of those titles than it did best-sellers.

"We used the term 'a world-class inventory' and didn't throw that around lightly," said Robert Teicher, the company's longtime fiction buyer. Gable prized merchandising displays dependent on several copies of a specific title, not just one or two. "We not only bought them, but bought them to be displayed," Teicher said. "So they would send us two copies, and Joe would get on the phone and say, 'I need seven copies. Or 10 copies. I need to display this thing.' "

They sold, too, he added.

"We were book people," he said.

iReport: Are there deals at Borders?

Falling in the river

Sharon Gambin had been a high school guidance counselor and, thanks to budget crunches, was pink-slipped twice in short order. While awaiting a new assignment, she applied at Borders.

As a child she'd fantasized about working in a bookstore -- about owning a bookstore. She once tried to talk her father into funding a bookstore. "Just craziness," she said.

"For me to get hired was like -- the thrill. Never realizing that what was happening for me personally was, how shall I say it? I fell in the river and I got swept up. As they say, I never looked back. It was a great match."

The store, she said, had its idiosyncrasies.

The receiving room was in the basement and there was no elevator, so books were stacked atop one another and carried upstairs. Nobody wore nametags. Gable gave pride of place to store recommendations over The New York Times best-sellers all the chain stores pushed. You could smoke, and everybody did. "There were ashtrays everywhere," said Gambin.

Be Kaimowitz, shown with partner Ed Vandenberg, "parked herself" at Borders to get an interview.

It could be a hothouse atmosphere; Teicher can think of at least five marriages that came out of the Ann Arbor store, including his own to Gambin. There were countless relationships, too, and stolen kisses in the basement.

The employees were proud of Borders' success. They shared in the profit of the store. They had a "funky little handbook" that specified Borders would be closed seven holidays a year so employees could spend time with their families.

"We'd have Christmas parties -- Joe would go around on Christmas Eve with an envelope, come up to you and shake your hand and say 'Thank you for your hard work,' " Gambin said. "On New Year's Eve he'd bring a bottle of champagne -- he'd say, 'Gambin, go to the liquor store next door and get some champagne' -- we'd lock the door and we'd have a toast."

Ann Arbor loved it back.

"Suddenly there were thousands of serious readers in town," staffer-turned-essayist Birkerts wrote in his book, "The Gutenberg Elegies." "They thronged the aisles of the store, asked questions, placed orders. The books had an aura, an excitement about them."

When the university wanted to show off the town, it took visitors to two places: Zingerman's, a legendary deli, and Borders. Locals knew they could find obscure philosophy texts and up-to-date computer science manuals, and they shared their love with the staff.

Jeanne Joesten remembers one couple, a pair of graduate students, who wanted the complete, multivolume edition of the Oxford English Dictionary as a wedding gift. They suggested putting the OED in a wedding registry, so friends could buy it for them a volume or two at a time.

"I went to Joe with the request and he grumbled, saying 'We're going to get stuck with (an incomplete set),' but he finally said, 'It's your baby.' So I did a memo to the staff and we set it up. And customers would come in and say, 'I want to buy volume H-L of the OED' and we'd sell it to them."

'Slowly, then all at once'

By the mid-1980s, the Borders brothers were eyeing expansion. The second Borders was in Birmingham, Michigan, in Detroit's northern suburbs, about an hour's drive from Ann Arbor. Before picking the spot, Tom and Louis engaged in a study. "They spent like a year there. They'd stand on a corner of Southfield and 13½ (Mile Road), clocking cars," recalled Teicher.

If the brothers were nervous about a second store, their worries faded quickly: "We spent years trying to catch up, business was so strong," said Teicher. "That was the power and the strength and the charm of Borders. Nobody in the Detroit metro area had seen that. They used to come to Ann Arbor to buy their books."

Pretty soon the budding chain opened a third store, in Atlanta, and a fourth store, in Indianapolis. By 1992, when the Borders brothers sold the chain to Kmart for about $125 million, Borders had 21 stores.

Some analysts have called the sale the first step in Borders' decline. Teicher doesn't agree.

"The sale to Kmart was completely transparent. The product of that was deeper pockets," he said. "We accelerated the store openings, which was always fun. ... Kmart had nothing to do with the decline of Borders. There was a synergy there that was positive."

The problems began three years later, he said, when Kmart spun off the Borders division -- which now included another Kmart book retailer, Waldenbooks -- and the company went public.

"When you become a public company, you have certain obligations, and in my opinion, when those responsibilities and obligations are not managed correctly, (they) lead to what we have now."

But during the '90s, the future looked rosy. Borders grew and grew, second only to Barnes & Noble. There was a Borders in Singapore. There was a Borders in the World Trade Center. The stock price flew high. At its peak there were more than 1,200 Borders and Waldenbooks stores, employing more than 30,000 people. Where did it go wrong?

Ask someone for the reason Borders went under and they'll give you a list. There was the Kmart deal and aftermath. There was the Borders Rewards program, which was offered free to customers, giving them little incentive to use it -- unlike B&N's plan, which charged a fee. Others point to the decision to sell CDs, which backfired when the music technology changed to downloads.

In fact, new technology began haunting the once-cutting-edge store. In 1998, Borders created a website but three years later handed its online business to Amazon; by the time Borders decided to reclaim its web presence in 2008, it had fallen far behind its competitors. Borders also was late to e-book readers, finally partnering with a Canadian company for its Kobo reader -- well after Amazon's Kindle and B&N's Nook took over the market.

Then there were misguided investments, overbuilding, personnel turnover. As Hemingway once wrote about a man going broke, it happened "slowly, then all at once."

"When Borders expanded, they brought in executives from supermarkets and department stores (all of whom insisted they were readers), and the result was a shuffle of titles and more downsizing against a backdrop of financial engineering, which only seemed to make matters worse," Public Affairs founder Peter Osnos wrote in The Atlantic.

For Gable, who moved to corporate in 1996 as a senior project manager and still witheringly refers to the executives as "the grocery guys," it was one frustration after another. At one point, he said, Borders spent millions renovating stores and then decided to create a model for the "store of the future," with different fixtures and carpeting -- none of which, according to Gable, could be retrofitted to Borders' 500 stores.

"They spend millions developing this stupid ('store of the future') and then six months later they pull the plug on it," he said. "So picture the money just pouring out. Then they get a new guy in. I say, 'What do we need?' (He says,) 'We need a new idea for a store.' 'Well, what could that possibly be?' 'Let's call it "the concept store." ' Let's have more consultants, and let's develop totally different fixtures -- metal fixtures -- and let's have a different layout, this time instead of a racetrack, people will find things by bumping into them!"

In other words, another "store of the future."

Meanwhile, the core of Borders' business, the focus on customer service and selection, had fallen by the wayside.

"You see the devolution here," said Teicher.

"Not only did they not pay attention to the selection," Gable noted, "they continued to downgrade the selection by emphasizing in its place things that were nonbook items. The point was that Borders was completely indistinguishable from B&N and the competition. The books that you could buy at Borders you could buy at Costco -- cheaper."

The customers, he said, knew it. Locals had always been sensitive about even the smallest changes -- Gambin remembers the horrified reaction when the Ann Arbor store switched from paper to plastic bags -- but the changes in philosophy were too much.

"A woman came up to me on the street a number of years after I left the (first) store, and she said, 'I have something to confess to you,' " Gable said. " 'You know I was a loyal Borders customer for over 20 years. I wouldn't even think of going anyplace else. I will never again go to Borders. ... It used to be I was able to find what I want, and if I couldn't find it myself someone would help find it for me. Now I go in there, and not only do they have this (nonbook) stuff, but nobody knows if you have the book or not.'

"The problem with the new guys," Gable concluded, "is they tried to take the book business, which is complex and boring, and make it simple and sexy."

'The treasure hunt'

The book business has never been easy. For a long time it was a relatively low-profit gentleman's game. Independents have often struggled; until the megastore trend, chains generally stocked a limited number of titles and focused on best-sellers. (Today's megastores still focus on the big names, giving The New York Times' best-seller list more play than Joe Gable would have liked.) It has remained a niche business. Even Amazon.com, which looms large over the industry, quickly started diversifying away from the book sales it was founded on; its recent commerce has been largely driven by electronics and general merchandise.

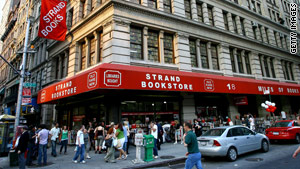

New York's 84-year-old Strand Bookstore has adapted to the times.

The Strand has survived by being creative. It has a thriving market in art books and advance editions. It has a strong presence on the Internet. During Borders' liquidation, the Strand reached out to Borders Rewards customers, honoring their discounts. After years coping with rent hikes and changing demographics, the store bought the building.

Bass still works the floor, a stocky man wearing a protective back brace and bold name tag, ready to answer questions from customers. That personal touch is the key, says his daughter and store manager, Nancy Bass Wyden.

"People want the tactile experience. They want the treasure hunt," she said.

"You try to keep some of the mystique of the old bookstore, but adapt," added Bass.

Indeed, bookstores today are dealing with challenges from technology and distribution, much like the music and newspaper businesses. They face competition from e-books, retailers such as Target and Walmart, and a variety of entertainment options unheard-of when the first Borders opened in 1971.

"Part of the problem is the activity of buying a book has become deculturalized. I can walk 10 minutes down the road from my office and buy the latest hardcover James Patterson book at (the supermarket) Stop & Shop," said publishing industry analyst Michael Norris of Simba Information. "Over the past 10 or so years, there are about 1,000 fewer chain bookstores, but 1,000 more Walmarts and Targets. And the Walmarts and Targets have no stake in the future of books."

Bookstore: A love story

For those who know No. 1, its demise is a knife to the heart.

Sharon Gambin, who had risen to No. 1's human resources manager and had the company catechism down pat, recalls a key incident with emotion.

"A few years ago, my heart was broken," she recalled. "They hired a man, who was a Borders GM, and gave him, the poor soul, the task of making Store 1 like every other store in the system."

Her voice breaks. "From that time, I went through a period of (asking), 'What am I doing?' "

Brian McDonald, left, and Joshua Fireman have been coming to the Ann Arbor Borders since they were children.

Brian McDonald and Joshua Fireman, two U of M undergraduates, went through the sci-fi section with equal parts glee and sadness. They weren't born when Borders was founded, weren't alive when it started expanding, yet they knew it as well as any old-timer.

"I remember coming here from elementary school," says McDonald, an area native.

"It's sad," agrees Fireman, who also grew up in southeast Michigan. "I'm buying as many books while I can."

Ann Arbor will survive. Downtown is thriving, an eclectic and walkable mix of shops and restaurants. Thanks to the university, a highly regarded hospital system and proximity to metro Detroit's auto and engineering firms, the city remains a sturdy blend of small business owners, free spirits and intellectuals. It has generally weathered the worst of Michigan's economic downturn, and a prime 40,000-square-foot spot is sure to have takers.

"We'll bounce back OK," said Diane Keller, president of the local chamber of commerce.

Still, she can't help but lament Borders' closing: "It was a warm place to go. It felt like your Borders."

"I think there is a sense of loss," said Marwil, the U of M history professor and author. "Given what's happening to the whole book trade, I don't think there has been quite the investment emotionally. If Borders had collapsed in 1998 there would have been a real sense of grieving. This is like the shoe dropping. And Borders had lost a quality of individuality. But still ... you can't help but feel twinges of what was."

Soon, Borders will join other names -- Booksellers in Cleveland, Oxford in Atlanta, Kroch's in Chicago, Scribner's in New York -- as ex-bookstores, their storefronts left as empty as desanctified churches. There is still a market for distinctive, customer-centric bookstores -- Ann Arbor has Nicola's about two miles from downtown -- but they're harder to come by nowadays.

"I think that the national chain store model will have some kind of future, but in order to be successful they can't have a cookie-cutter approach for their retail locations," said industry analyst Norris. "There has to be something for local books and local authors other than a 2-foot-by-2-foot card table on the second floor. The stores should have a personality."

Gable has wiped his hands of it. He's been gone now for three years. He recently stopped by No. 1 and left feeling "bitter and angry." "The loss to book lovers is probably irreparable," he told CNN in an e-mail.

Gambin prefers to remember better times and a wealth of colleagues. It wasn't so long ago, she says, that the growing company was still filled with people who had roots at No. 1, friends who had started in the basement and had suddenly found themselves on top of the world.

More recently, she says, she tried to focus on the "books and the people" -- she repeats the phrase twice, like a mantra -- "so I could transcend the rest of the crap."

"But I grieved for many years and was angry for many years," she said.

And then came the day a year or two ago when she thought she couldn't do it anymore. She got a part-time job at a local college. Still, she couldn't leave Borders behind, working part-time. She's remained during the liquidation, helping out to the end.

Gambin is 64 now. She has spent almost half her life at Borders. She struggles to put a career, a business, a love in context.

"You're married to something and one day you wake up and it's a different person or something's different about them, and you keep hoping the good parts are going to come back," she said.

So let's try this again.

Once upon a time ...

"Memento mori"

(Me)

0 comments:

Post a Comment